- Home

- Joseph McCullough

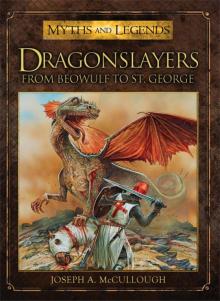

Dragonslayers

Dragonslayers Read online

DRAGONSLAYERS

FROM BEOWULF TO ST. GEORGE

AUTHOR: JOSEPH A. MCCULLOUGH

ILLUSTRATOR: PETER DENNIS

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

ANCIENT DRAGONSLAYERS

Cadmus, Founder of Thebes Hercules and Ladon, the Hundred-headed Dragon Daniel of the Lion’s Den

NORSE DRAGONSLAYERS

Sigurd the VÖlsung Beowulf

HOLY DRAGONSLAYERS

St. George and the Dragon Pope Sylvester I St. Carantoc and King Arthur

MEDIEVAL DRAGONSLAYERS

John Lambton and the Lambton Worm Dieudonné de Gozon, Draconis Extinctor Lord Albrecht Trut Dobrynya Nikitich and Zmey Gorynych

DRAGONSLAYERS FROM AROUND THE WORLD

Manabozho and the Fiery Serpents Pitaka and the Taniwha Agatamori

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

INTRODUCTION

This is a book of battles, of desperate fights between the greatest heroes of myth and legend and mankind’s most ancient and dangerous foe, the dragons. These titanic serpents, with or without wings, or indeed, legs, have haunted the dreams of humanity since our earliest days. In our oldest myths, the gods themselves battled these monsters in an effort to bring order out of chaos, and light out of darkness. In Ancient Babylonian tales, the god Marduk fights against Tiamat, the dragon of chaos. According to the Ancient Greeks, the god Zeus struggled against Typhon, the ‘Father of all Monsters’, while the sun god Apollo slew the great dragon Python. This last tale is perhaps a reflection of the Ancient Egyptian story where the sun god Ra battles the god of chaos and darkness, Apep, usually depicted as a great serpent or dragon. According to the myths of the Ancient Norse, the struggle against the dragons will continue until the end of time, when Thor will slay Jōrmungandr, the Midgard Serpent, as part of Ragnarök, before dying himself from the effects of the serpent’s poison.

It is those great battles in the heavens that serve as the backdrop for the stories presented here. This is a book about heroes: men who, despite their mortality, faced off against the dragons and used their strength, skill, and cunning to overcome their enemies. Today, there are literally hundreds of myths, legends, and folktales about dragonslayers. Some of these come from historical, or semi-historical sources; others survive as mere fairytales. To collect them all would be the work of more than one lifetime.

Presented here are the most famous, important, interesting and entertaining stories about dragonslaying. Each tale is retold using modern language and modern storytelling sensibilities, but attempts to stay as true as possible to the original source material. Accompanying each tale is the essential information about the myth or legend: its sources, its historical basis, its development, and its continuing legacy in the modern world.

The story of the dragonslayer is usually considered a European one. It begins in the myths mentioned above and has its strongest roots in the Classical Greek and Ancient Norse stories. These were then filtered through the rise of Christianity, until stories of dragonslayers became part of the make-up of medieval European culture. Although there are dragonslaying stories from other parts of the world, and these will be touched upon in the last chapter of the book, the vast majority of stories, and the enduring legacy of the fight between men and dragons, comes from the European tradition.

Today, thanks in no small part to the writings of J.R.R. Tolkien and the early role-playing game, Dungeons & Dragons, dragonslayers have once again become a staple part of modern storytelling and appear in books, comics, and movies too numerous to mention. But there were times, in centuries past, when people truly believed in dragons, when deadly giant serpents with poison breath could lurk in any hole or cave. Those were the days of the great heroes. Those were the days of the dragonslayers.

ANCIENT DRAGONSLAYERS

Many of the early stories of men battling against dragons come from the heroic tales of mythic Greece. In fact, the word ‘dragon’ derives from the Greek word ‘drakon’, meaning ‘a creature with scales’, usually a ‘serpent or sea-monster’. Unfortunately, this immediately leads to a problem. When the Ancient Greeks used the word ‘drakon’ they were not always referring to a creature that modern readers would recognize as a dragon. They could have meant a simple snake or even a shark-like sea-creature. For example, the ancient hero Perseus is sometimes said to have used the head of Medusa to rescue the princess Andromeda from a dragon. However, this is a misreading of ‘drakon’, for the creature described is truly a sea-monster and has no specific dragon-like qualities beyond having scales.

Despite this confusion, the tales of Ancient Greece are full of dragons in the form of giant serpents, often possessing multiple heads and breathing poisonous fumes. Unlike later myths, where dragons seem to have become a true species, almost all of the Greek examples are unique creatures, the offspring of gods, Titans or other monsters. Also, unlike later dragons, these giant serpents are not specifically evil. They are dangerous and usually no friend of mankind, but they embody no specific malice.

While many of the ancient dragonslayer stories in Western culture come from Ancient Greece, there are a few tales of heroes taking on dragons or serpents in other cultures, most notably Celtic and Hebrew, though most of these encounters are just diversions from other adventures, or side-quests from the main story.

Presented below are three of the best known, and most fully elaborated, stories of ancient dragonslayers. Two, the tales of Cadmus and Hercules, come from Ancient Greece, while the third, Daniel of the Lion’s Den fame, can be found in the Old Testament of some bibles.

Cadmus, Founder of Thebes

Long before the fall of Troy, the ill-fated King Agenor, son of the sea-god Poseidon, sat on the Phoenician throne and ruled his people with wisdom and justice. The king had three sons, Cadmus, Phoenix, and Cilix and a daughter, Europa, and for many years they lived happily. However, as Europa grew to womanhood, her radiant beauty grew so nearly divine that Zeus himself came down from Olympus and bore her away. When King Agenor learned of his daughter’s disappearance, his grief overwhelmed him. In his madness, he commanded his three sons to go out and search for their sister and not to return unless they found her.

Cadmus slays the dragon by Hendrick Goltzius.

Despite his father’s unkind order, Prince Cadmus gathered together a group of companions and set off on this quest. For months he led his men through many adventures, through battles and hardships, but not one clue did they find concerning the missing Europa. In desperation, Cadmus took his men to Delphi in Greece, to consult with the famed Oracle of Apollo. There, where Apollo had slain the dragon, Python, the Oracle instructed Cadmus to abandon his quest, for he would never find his sister. Instead, he should go forth and follow the first animal he encountered until it laid down to rest. In that spot he should found a city.

Troubled by the failure of his quest, Cadmus left the Oracle and returned to his companions. Soon after, he spotted a lone cow, with the sign of the moon on one flank, and decided to follow the beast. For days, Cadmus trudged along after the heifer, which never stopped and never rested, until, finally, it settled down in Boeotia. The men rejoiced that they had reached the end of their travels, and Cadmus determined to make a sacrifice to the goddess Athena in thanks. Spying a nearby spring, Cadmus sent his companions off to fetch water, while he prepared the sacrifice.

Cadmus attacking the dragon by Hendrik Goltzius. (The Bridgeman Art Library)

Cadmus’ men grabbed their pitchers and headed up to the spring. The water there flowed out of a narrow crevice of rock, close packed with dense vegetation. As the men knelt down to fill their pitchers, a piercing shriek echoed around the rocks, and a great serpent slithered out from the foliage. Its scaly head rose up until it peere

d down upon the men. A golden crest gleamed on its head, while a three-forked tongue flickered between its sharp fangs. It spewed out its venomous breath in a choking cloud, then lashed out at the men as they gasped for air. Some men it snatched up in its deadly jaws, others it crushed to death in its coils. A few men managed to draw their swords and fight back, but their bronze blades bounced harmlessly off the dragon’s scales. In a matter of moments, the brave men who had followed Cadmus across hundreds of miles had all been killed.

Meanwhile, Cadmus had finished his preparations for the sacrifice, and begun to worry that his friends had not returned. As the sun started down in the sky, Cadmus picked up his spear and his iron sword and started after them. When Cadmus reached the spring, he stared in horror at the carnage before him. His faithful companions lay in slaughtered heaps, their bodies torn and crushed. And there, in the midst of it all, the great dragon lay coiled, licking at the bloody wounds of the fallen.

Filled with rage, Cadmus cried out, ‘My loyal friends. I shall either avenge your deaths or become your companion!’ Then, tearing a great rock from the ground, Cadmus flung it at the dragon. The rock shattered against the scaly hide. Once again, the dragon reared up, gave its shrieking cry, and lunged. Cadmus dodged aside, then drove his spear between the dragon’s scales until the spear tip burst out of the serpent’s back. The creature thrashed from side to side, ripping the spear from Cadmus’ hands and shattering the handle, but the spearhead remained fixed in its spine. Then Cadmus drew his iron sword. He stabbed repeatedly at the creature’s head, driving it back, until, with a mighty lunge, Cadmus drove the sword through the creature’s throat and pinned it to a tree behind. For a moment the great serpent writhed in place, before it died upon the tree.

As the life faded from the dragon’s eyes, the goddess Athena appeared beside Cadmus. She commanded the hero to cut out the dragon’s teeth, give half of them to her, and then plant the rest in the ground like seeds. Cadmus did as he was instructed, then watched in amazement as armed men grew out of the ground where he had planted the teeth. Cadmus reached for his sword, but one of the newly born men told him to keep back and take no part in their affairs. So Cadmus just watched as these earth-born men attacked and killed one another, until only five remained. Then Athena appeared again and ordered the men to stop fighting and join with Cadmus. With these new companions, Cadmus went back to where the heifer had sat down. He made his sacrifice and founded a city with the help of his five companions. He named the city Thebes, and it would become one of the richest cities in the world.

Cadmus and the dragon by Francesco Zuccarelli. (Rafael Valls Gallery / The Bridgeman Art Library)

The story of Cadmus, his battle with the dragon, and the founding of the city of Thebes can be found scattered throughout the works of the Ancient Greek and Roman writers including Apollonius, Apollodorus, and even Homer. Probably the most complete and coherent version of the story is presented in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, from which the above version is mostly drawn.

In many versions of the story, the dragon killed by Cadmus was sacred to Ares, the god of war, and Cadmus is forced to serve the god for several years by way of restitution, before being allowed to return to Thebes and marry the goddess Harmonia. In this case, the story becomes a rare example of a tale in which the dragonslayer is actually punished for his victory. Also, some versions have Cadmus transformed into a dragon as punishment, while others say that the transformation occurred much later in his life, when he taunts the gods because of his ill luck. In either case, the story is one of the few that has a dragonslayer himself becoming a dragon.

JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS

Probably the most famous dragon in Ancient Greek myth and legend is the giant serpent that guards the Golden Fleece in the story of Jason and the Argonauts. In some versions of the tale, Jason does slay the dragon, but in most, the dragon is put to sleep, either by the witch Medea or by Orpheus the musician. To make matters slightly more confusing, the dragon teeth sown into the ground by Jason do not come from the guardian of the Golden Fleece, but instead are the other half of the teeth from the dragon slain by Cadmus which were taken by Athena.

This is not to say that Jason and the Argonauts are not dragonslayers. According to a Slovenian legend, Jason and the Argonauts battled with a dragon near a swampy river, on their journey back with the Golden Fleece. After slaying the dragon, Jason founded the city of Ljubljana, the modern capital of Slovenia. His feat is commemorated by a quartet of dragon statues that guard the corners of ‘Dragon Bridge’ in the centre of Ljubljana.

The exact origin of this legend is unclear, but it almost certainly owes more to medieval city-founding legends than it does to the tales of Ancient Greece.

Apparently, in some versions of the story, Jason is not so successful when facing the dragon. In this ancient artwork, the goddess Athena commands the dragon to regurgitate the unfortunate Argonaut.

Cadmus and the Dragon. According to Herodotus, the battle between Cadmus and the dragon occurred several generations before the fall of Troy. This artwork depicts Cadmus in this time period, using weapons and armour appropriate to a warrior of the Aegean Bronze Age.

Thankfully, the story of Cadmus generally ends happily, with Zeus taking Cadmus and his wife, Harmonia, away to the Elysian Fields.

These days, Cadmus is more often mentioned for his other mythical endeavour, the introduction of the Phoenician alphabet to Greece as told by Herodotus in his Histories. Cadmus the dragonslayer is mostly forgotten; his legend overshadowed by those of the later Greek heroes, most notably by the greatest Greek hero of them all, the dragonslayer Hercules.

Hercules and Ladon, the Hundred-headed Dragon

For eight long years, Greece’s greatest hero, Hercules, had laboured as a servant for King Eurystheus, a punishment for the murder of his own sons in a fit of madness. Early in his servitude, Eurystheus had ordered Hercules to kill the Lernaean Hydra, a terrible dragon-like creature with nine heads, eight mortal ones, and one immortal, all of which breathed a poisonous breath. Riding the chariot of his comrade Iolaus to the creature’s lair, Hercules forced it to emerge by hurling flaming brands into its cave. He then charged the monster and battered off several of the hydra’s heads with his mighty club, but for every head he severed, two more quickly grew in its place. So in the midst of the fight, he commanded Iolaus to take up a burning brand and sear the stumps of the heads as he battered them off. This kept them from regrowing. Eventually, only the immortal head remained. Hercules tore off this last head with his bare hands, buried it in the ground, and placed a great boulder on top of it. He then ripped open the hydra’s body and soaked his arrows in its deadly, venomous blood.

Statue of Hercules and Ladon outside of Waldstein Palace in Prague.

Many years had passed since that fight, and many deeds had been accomplished. In that time Hercules had killed the Erymanthian Boar, captured a golden-horned stag, defeated the triple-bodied Geryon, and taken the belt of Hippolyta, queen of the Amazons. He even wrestled with Cerberus, the three-headed dog that guarded Hades, and defeated the creature despite the sting of its dragon-like tail. Recently, he had joined with the Argonauts on their quest to recover the Golden Fleece, before they had abandoned him on the journey.

Now, one last task remained to him, one last labour to secure his freedom. King Eurystheus had commanded him to fetch the golden apples of the Hesperides, which were guarded by Ladon, a dragon with one hundred heads. And so Hercules set out alone, so that no one could accuse him of having received help in this, his final task. He took with him only his great club, his bow and the deadly arrows soaked in hydra blood. He dressed in the skin of the Nemean Lion, which he had slain. By ship, he crossed the Mediterranean to Libya and then travelled on foot through the Atlas Mountains. Without food or water, he journeyed under the sun’s cruel heat, until he stood on a peak above the Garden of the Hesperides.

With a grim face, cracked with thirst, Hercules strung his bow and marched down int

o the garden. From his quiver, he drew a long arrow, its head stained with the poison of the hydra, and set it in his bow. In the garden ahead, he spied his enemy coiled around the tree of golden apples, its long serpentine body ending in a waving mass of long-necked dragonheads. Each head called with a different voice, producing a painful cacophony, a swirling storm of language. By willpower, Hercules blocked out the sound. He raised his bow to his eye, drew back the bowstring to his ear and loosed. The arrow streaked out and exploded through the writhing mass of heads, severing two, and causing the dragon to rear back in pain. Again and again, Hercules nocked his arrows, drew back the bowstring, and let fly. His shafts buried deep in the dragon’s body. It crawled forward, but under the barrage of arrows, each soaked in deadly poison, it wavered then fell. It crashed down amongst the trees of the garden, and its heads fell silent.

Hercules neither smiled nor frowned at the destruction he had brought to the garden. Without a word, he walked past the dying dragon and found the golden apples he’d come to fetch. He would return them to King Eurystheus, and then he would once again be free to chart his own destiny.

It is impossible to write a history of dragonslayers without covering Hercules, and yet he is one of the most confusing and controversial heroes to claim the title. For most heroes, their fight with a dragon is their defining moment, the deed that grants them legendary status. But Hercules is a hero without equal, a demi-god who accomplished so many feats and who slew so many monsters that no one story, no one deed, defines him. Thus, many of his triumphs are only recorded briefly and details are lacking.

Dragonslayers

Dragonslayers